I’m thrilled to welcome multi-award-winning author Charlotte Betts to my blog today.

Charlotte, the author of a number of romantic historical novels, draws inspiration from the stories of strong women at turning points in history. Her careful historical research brings to her writing an evocative sense of time and place. She is currently working on The Spindrift Trilogy, set in an artists’ community in Cornwall at the turn of the twentieth century.

And now, over to Charlotte!

* * * * *

Bathrooms and bogs – Victorian and Edwardian bathrooms.

‘Soap – The yardstick of civilisation.’ Sigmund Freud

Wash basin

During the 1860s and 1870s, mains water, provided by municipal or private companies, was supplied to most towns and cities. This triggered an important change in the design of new houses and bathrooms, and fixed sanitaryware began to appear in some upper and middle class townhouses. In existing houses, dressing rooms were sometimes converted into a bathroom.

Copper gas bath

Despite a piped water supply, a servant was still required to carry cans of hot water upstairs, at least until the invention of a ‘gas bath’. The upper-middle classes proudly installed models named the ‘Prince Albert’ or the ‘General Gordon’. These had a gas or solid fuel stove to one end of the bath, or a gas burner underneath, and took half an hour to heat. I can’t help wondering how many Victorian bottoms were unexpectedly burned in the bath!

Geysers were the next invention. These heated tanks were fixed to the wall over the bath or a wash basin, and after several fierce gurglings and a series of minor gas explosions, spouted forth clouds of steam and a gush, if you were lucky, or a trickle of hot or tepid water, if unfortunate. By the 1880s, hot water would be supplied from the kitchen range’s back boiler and stored in a copper cylinder in the loft.

Late Victorian Bathroom

Some of the great country houses owned by aristocratic families were surprisingly late to add bathrooms with a hot water supply. Perhaps this was because servants were cheap and plentiful, whereas the upheaval of installing plumbing to the distant reaches of the upper floors was an expensive exercise. I doubt that aristocrats considered their servants’ exhaustion as they toiled up several flights of stairs carrying can after can of hot water, and then had to carry all the slops down again later. The male members of the landed gentry may have developed a masochistic streak from all those cold baths at boarding-school and fostered a lingering suspicion that warm baths were for degenerates. In the Edwardian era, there was an influx of American heiresses seeking a titled husband, who were horrified at the thought of inhabiting cold and draughty stately homes. Once the ring was on their finger, they insisted on new bathrooms with efficient plumbing and plenty of hot water.

Terraced house

A new type of house with a bathroom was being built for the lower-middle classes by the 1890s. Smaller than the detached or semi-detached villas for the middle classes, it was larger than a terraced house for the working classes. They usually had six to nine rooms with a bathroom, including a pedestal WC, fitted between the middle and back bedroom. Some houses might have had an additional WC outside for the daily help.

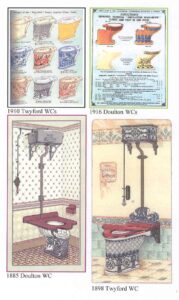

1885 Doulton WC

In many industrial towns, working class terraced houses usually had a cold tap in the kitchen and a privy outside in the yard beyond the coal shed.

Hopper-lavatory

There would be a pail of ash or water beside a wooden seat with a hole cut into it, fixed over a hopper that drained into a tank beneath. This was emptied through a small door from a rear alley by the night soil men. Baths would be taken in a galvanised hip bath in the scullery or in front of the range in winter. The man of the house used the water first, followed by his wife and children.

It wasn’t until 1918 that legislation was passed to provide bathrooms with a hot and cold water supply to new-build houses for the working classes. Existing properties remained without such luxuries for many decades afterwards.

Well

Homes in the country, both large and small, had to wait much longer for a piped water supply. I remember staying with my great aunt in the 1960s, who drew her water from the well in her cottage garden. This was filtered through a large gravel-filled fireclay cylinder and drawn off from a little brass tap at the bottom. Water for washing was heated in kettles on the Aga, and there was a spotlessly clean privy in the garden with a scrubbed pine seat.

Privy

In 1971, I bought my first house, a middle-terraced cottage in the country and, although there was a cold tap in the scullery, there was no bathroom. I did have, however, a licence to pass on foot to one of a block of four WCs on a small plot of land behind the garden. Despite these facilities, I lost no time in converting the box room into an upstairs bathroom!

Chamber pot

The Victorians considered that ‘Cleanliness was next to Godliness’ and Sigmund Freud said, ‘Soap is the yardstick of civilisation’. That was all very well if you had servants to fill your weekly bath, bring hot water to your dressing room every morning, empty your chamber pot and carry away your dirty water. If you were from a poor working class family, cleanliness was infinitely harder. Can you imagine what it might have been like, trying to keep clean from one outside tap when you lived in a two up, two down with, perhaps, ten siblings and a father who worked down the mine?

Relaxing bath

Today a bathroom is considered an essential room in the house. It isn’t only a place to wash, but also a private retreat, with a key, where you might light candles around the bath while you soak away the cares and troubles of the day. Perhaps it’s fitting that history has come full circle as we seek to recreate the sybaritic atmosphere of peace and relaxation that the Romans introduced to the British Isles.

* * * * *

Thank you, Charlotte!

Charlotte lives on the Hampshire/Berkshire borders in a 17th Century cottage in the woods. A daydreamer and a bookworm, she has enjoyed careers in fashion, interior design and property. She is a member of The Romantic Novelists’ Association, The Society of Authors and The Historical Novels Society.

She says, ‘To be the first to hear about my new releases and my writing life, please visit www.charlottebetts.co.uk and subscribe to my mailing list. I promise not to share your e-mail and will only contact you when I have a news update or a new book is published.’

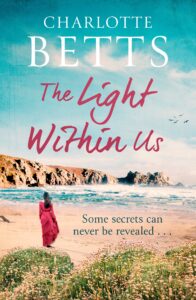

The Light Within Us from award-winning author Charlotte Betts is the first book of the Spindrift Trilogy.

Talented artist Edith Fairchild is looking forward to a life of newlywed bliss with her charismatic husband Benedict. He recently inherited Spindrift House near Port Isaac and Edith is inspired by the glorious Cornish light and the wonderful setting overlooking the sea. But then happiness turns to heartbreak. In great distress, Edith turns to an artist friend for comfort. After a bitterly-regretted moment of madness she finds herself pregnant with his child.

Too ashamed to reveal her secret, Edith devotes herself to her art. Joined at Spindrift House by her friends, Clarissa, Dora and Pascal, together they turn the house into a thriving artists’ community. But despite their dreams of an idyllic way of life creating beauty by the sea, it becomes clear that all is not perfect within their tight-knit community. The weight of their secrets could threaten to tear apart their paradise forever . . .

Buy The Light Within Us here: mybook.to/LightWithin

Follow Charlotte on Twitter at @CharlotteBetts1 or on Facebook at Charlotte Betts – Author, or on Instagram charlottebetts.author

To read more fascinating posts by Charlotte, please note the following dates and locations of her book tour:

And some final words from me, Stay safe and stay well!!

I loved this post, Charlotte. I especially liked the late Victorian terrace house because it is exactly like the first house we owned in Hanwell, Ealing. I also was interested in your first cottage house with outside loos.

It was very interesting reading! Sanitary issues in the past are always a matter of curiosity to me.

I shall pass your comment on to Charlotte, Gisele. Thank you for it. I’m the same as you. These matters are interesting, as they are a part of the daily life of the people who feature in our fiction, and it jumps a reader out of the story if they read something that implies that in 17th century England, for example, there were flush toilets and hot running water upstairs and downstairs. Charlotte’s post was most interesting. 🙂